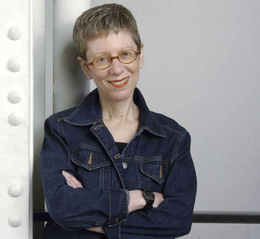

Terry Gross has earned her reputation as one of her generation’s most respected interviewers. The longtime host and co-executive producer of “Fresh Air with Terry Gross,” a contemporary arts-and-issues radio program produced locally by WHYY-FM and syndicated to more than 450 public radio stations through National Public Radio, is well known for her no-stone-left-unturned preparation and mastery at engaging A-list guests in intimate conversations.

An estimated 4.5 million people listen to “Fresh Air” countrywide and in Europe through the World Radio Network. (Local listeners hear the show weekday afternoons at 90.9 on the FM dial.) Her guest list reads like a “who’s who” of actors, musicians, authors and political giants, among others. Her well-publicized scraps with ill-mannered guests such as rock star Gene Simmons, who made crass and some might say misogynistic remarks to Gross, and conservative-politics icon Bill O’Reilly, who famously walked out of his interview, made national headlines. Some of her more enlightening interviews were fodder for her 2004 book, “All I Did Was Ask: Conversations with Writers, Actors, Musicians and Artists.”

Gross, a Brooklyn native who made Philadelphia her home in the mid-1970s, agreed to sit on the other side of the microphone to talk about the Yankees, her own celebrity and, above all, the art of the interview.

Q: The combination of your delivery, the smoothness of your voice and thorough preparation make your interviews feel very intimate. I read that you still get nervous before each interview. Was there ever a time, even early on, when you thought, “This isn’t for me”?

I get nervous about feeling under-prepared because there’s never enough time to prepare as much as I’d like; I don’t get nervous about a person being famous. Was there ever a time when I thought I was no good? Yes, but I liked it so much I thought that as long as they allow me to keep doing it, I’m going to keep doing it.

I started as a volunteer at a station in Buffalo, and I knew nothing about radio; I knew nothing about journalism; and back then you couldn’t accuse me of having a radio voice. … I learned on the air, and it was absolutely terrifying. My brother was living in Buffalo at the time, and I didn’t tell him I was going to be on the radio because I figured it was going to be so bad that it should not be shared with someone you love.

I got a paid job here in Philadelphia at WHYY, which was then WUHY, in 1975. In Buffalo I was getting paid a graduate assistantship, making probably $3,000 a year, and you couldn’t live on that no matter how Spartan a lifestyle you lived. All of a sudden I was in Philly, with a real job with real benefits, like life insurance, and I never expected that. I was just thrilled.

You’ve come a long way since then and have been hosting “Fresh Air” for more than 30 years. I’m assuming you must love it to the point that it feels like much more than a job.

I’m trying to think of a word other than “job.” It’s like a longtime commitment, like a practice or a discipline in a way. There’s a lot of repetition; every day I get up and write interview questions and prepare for the show, but every interview is different unless you’re having [a guest] on for a second time. So there’s this constant sense of change even though there’s something repetitive about the routine. In that sense it’s like a discipline. … It’s been my life for so long, or at least an encompassing part of my life.

I imagine a question you must hear a lot has to do with which guests are among the most memorable. Gene Simmons is probably right up there, even if it’s for the wrong reason, but who else sticks out in memory?

In the Gene Simmons sense, there’s Bill O’Reilly [host of Fox News’ “The O’Reilly Factor”], who walked out on me. … As for memorable interviews in terms of the positive experiences, I think back to all those interviews with [author] John Updike and the honor of talking to him. It’s so sad knowing he died and that there won’t be another interview. We worked so hard to get the first interview with him, because he was so reclusive with the press, and then we were able to interview him several other times after that [before his 2009 death], and you almost took it for granted.

[New Jersey-born author] Philip Roth is another one. There were a bunch of times I interviewed him, most recently this fall for his latest book. I think what I like about great writers like Updike and Roth is that they offer insight into the human condition; they see inside people. Great actors have that ability too, though they’re usually not as expressive as great writers are.

Have you ever been star struck during an interview?

I’ve felt that way sometimes. I’ve interviewed [Academy Award-winning composer] Stephen Sondheim, who’s another of my real heroes, and he doesn’t particularly like being interviewed. I knew that going into it, which probably made me uncomfortable, so we had this uncomfortable feedback loop. It doesn’t help to be star struck. You want the listener to know they’re in good professional hands, and they can sense it when you’re acting more like a fan than an interviewer.

You interviewed Anne Hathaway earlier this year for her film “Love and Other Drugs,” and she alluded to the fact that you two were not in the same studio during the interview. I’ve always envisioned two people in the same room, facing each other, because the conversations are so intimate. Does not seeing the person face to face actually help you in a way?

It’s seldom the case [doing face-to-face interviews], and it used to throw me a lot. I was used to being able to see a person’s face and know when they were done with an answer; I would feel like I’m interrupting them. … There might be some advantages to not seeing each other, like not judging each other based on the way the other person looks. It’s pure radio; we’re just voices to each other and to the listeners, and I think for me one of the advantages is that I’m able to ask harder questions when I’m not looking in the other person’s eyes. I feel like I’m receptive to people’s emotions. If I’m doing a political interview I know I have to ask tough questions. In that case I won’t hold back from pushing further even if I feel like I’m making them uncomfortable.

You have a knack for asking delicate questions in a very natural way, using phrases such as, “I hope it’s OK to ask.” I remember a 2008 interview with the late comedian Robert Schimmel, in which you challenged him for going back to his wife to help him through his bout with cancer and then leaving her for another woman once he recovered.

I really try to respect people’s privacy, but someone like Schimmel, who makes his private life the subject of a memoir, is putting it on the table for discussion. It becomes my job to further the discussion and maybe take it a step deeper. … With the Schimmel interview, I knew every listener was thinking, “Is [what he did to his wife] right? How can he do that?” The elephant is on the table, so if I don’t ask, I feel like I’m not doing the subject justice.

Do you have different rules for different interviewees, or do you approach each interview the same?

I do approach each one differently. … I also have different rules with political interviews. On the rare occasion I get to speak with someone in elected office or in a position of political power, there might be instances where they have taken a position or voted in a way that’s going to affect our lives but will be contradictory to how they live their lives. Then I won’t say, “If it’s too personal, let me know.” A classic example might be a politician having a gay affair but voting against gay rights.

Is being a good interviewer more about being prepared or more about understanding the nature of people and how people think, or merely a healthy dose of self-confidence?

Doing a good interview is a combination of preparation, genuinely caring about the subject and bringing knowledge to the interview through your preparation with a genuine curiosity. There’s also the matter of flexibility, that no matter what path the interview takes regardless of what you planned, you know how to and are willing to follow them, so that when someone throws a curveball you can be in the moment and hit it.

Do you have complete autonomy over which interviews you do and those you don’t?

I definitely have veto power. We as a team believe the person doing the interview can say, “That’s not for me.” … I work with very strong-minded, opinionated producers who think they know what is best for the show. I give them space to persuade me, because I can be pretty closed-minded sometimes. But I like that they can come back to me and say, “Here’s why you’re wrong.”

The interviews we hear on your show are almost always produced rather than live, so what don’t we get to hear that gets left on the cutting-room floor, so to speak?

What gets left on the floor is a combination of really boring questions and answers, long-winded and confusing answers, me saying, “Gee, I really said that in a confusing way; let me say that again,” or me tripping over my tongue, or guests tripping over their tongue. Mostly, though, what we’re trying to do through editing is distill the interview down to the most interesting parts.

You have a peculiar kind of celebrity because your voice is so distinctive and is heard across the country. Has there ever been a time when you’re in a restaurant or otherwise out in public and someone hears your voice and thinks they somehow know you but can’t quite figure it out?

There are times in a restaurant when I’m with someone having a really personal conversation when someone will come up [because they recognized her voice] and say, “I really like your show.” I’m left there thinking: What have I just said and shared with the world? Most NPR listeners are just so nice … and I really enjoy it when listeners introduce themselves.

You grew up in Brooklyn but have been in the Philadelphia area for, I think, 35 years. Why has WHYY—and Philadelphia, for that matter—been such a good home?

I came here in ’75, and Danny Miller [now the show’s co-executive producer] joined as an intern in ’78. The show became fun in a way it hadn’t before, because it felt like I had a partner who really enjoyed working on it. … I didn’t expect to stay in Philadelphia a long time. I was then and am still astonished that I was able to keep a show going this long and keep it going in conjunction with a longtime producer in Danny Miller. The show was able to grow, and I felt like I was growing as a radio professional.

Also, my husband is from Philly. WHYY has made a nice home for us, and I’m very grateful for that. … Technically, we could do the show anywhere, as long as it has a satellite and an ISDN line. We could do it almost anywhere, but you want a home that understands the show, and we’ve gotten that here.

I have to ask, considering your New York roots: Phillies or Yankees?

I’ll say Phillies but will honestly say I don’t usually follow baseball. My husband loves the Phillies and gets very excited about them, and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t get a little caught up in it myself.