Breaking the Mold

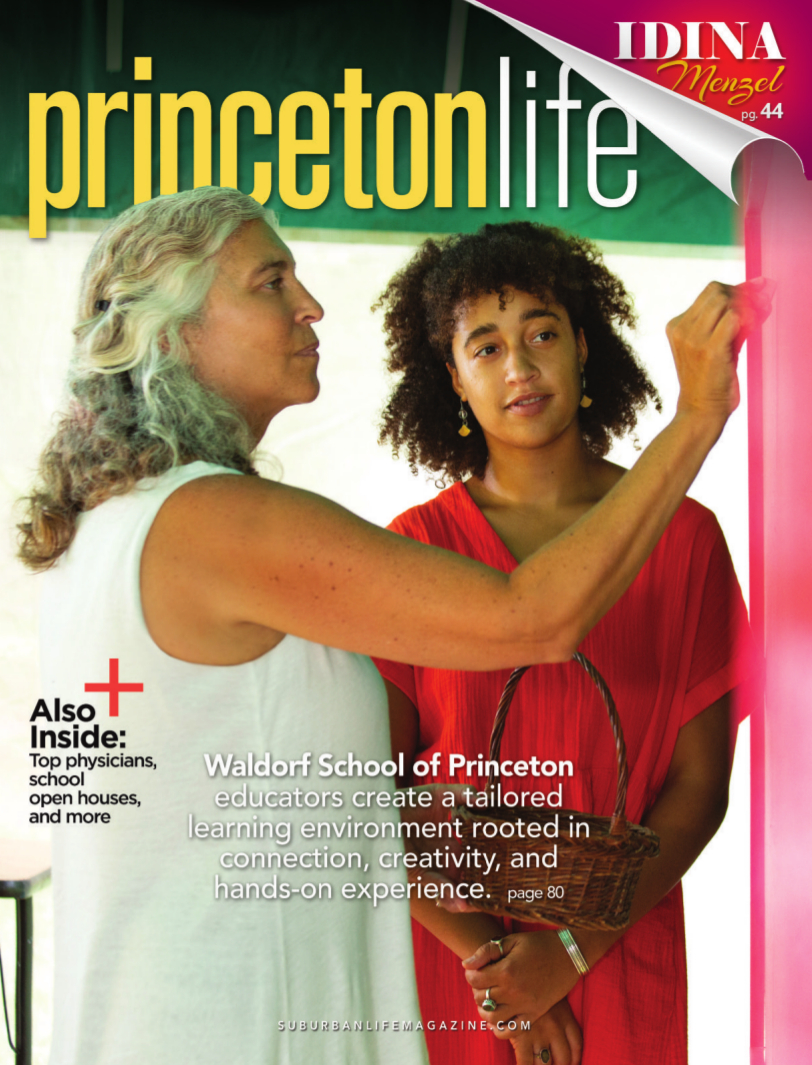

Waldorf School of Princeton students benefit from an individualized learning environment rooted in connection, creativity, and hands-on experience.

Zoë Brookes knows firsthand how difficult it can be to have a child who isn’t thriving in school. When her son was in fifth grade, he felt as though he did not fit in, so much that he asked to go to school somewhere else. A search of viable alternatives revealed the Waldorf School of Princeton. Upon enrollment, he felt as though he had found a home.

“For the first time, he felt truly ‘seen’ as a human being,” Brookes recalls. “He was always really good at math and science, and while the Waldorf School gave him an opportunity to build on those strengths, it didn’t give him a pass on his weaknesses. The school experience taught him that he had to come to terms with his whole self as a human being.”

Brookes’ son graduated from Princeton University this past spring. His success story is one of many that illustrate the transformative effect of a Waldorf education.

Brookes recently became the new school administrator for the Waldorf School of Princeton. In addition to her own family’s experience, she brings to her new role a robust business background. She earned an MBA from London Business School, and garnered extensive experience in the management of nonprofit organizations, some of which focused on serving children. Brookes believes she also brings to the school “a heart for experiential learning.”

The Waldorf School of Princeton is one of the approximately 150 Waldorf schools across North America, and the only one in the Garden State. As traditional schooling continues to move in the direction of standardized test taking as a means of measuring proficiency, Waldorf schools hold steadfast to the belief that children learn best through the experience of thinking, feeling, and doing. Integration of the academics, arts, and practical skills is at the heart of curriculum and methodology, fostering the lifelong love of learning needed to meet life’s challenges.

“I’ve long been frustrated that schooling is becoming increasingly regimented, and teachers are losing authority over the work they do in their classrooms,” Brookes says. “Teachers find they are prevented from using their own sense of judgment and their passion, as they increasingly must just follow a prescribed way of teaching.”

Karen Atkinson believes this area may be the one in which a Waldorf education shines brightest.

“We want teachers to be inspired to tap into their own creative forces, as that is what makes learning meaningful and fun for students,” says Atkinson, who teaches third grade at the Waldorf School of Princeton. “We provide opportunities for teachers to find renewal and inspiration outside of school through ongoing professional development workshops and conferences and encouragement to visit other Waldorf schools.”

The Waldorf approach emphasizes the fact that students learn best when they do not have to conform to a specific mold. Furthermore, Waldorf schools take a creative approach to educating while prioritizing the importance of human-to-human connection.

“We see our roles as educators as leading our students joyfully through education so that they can reach their highest potential, not only as students but as human beings,” Atkinson adds. “We are guiding our students with creative and meaningful experiences so that they can go beyond any obstacles that might be in their path to learning. And we want them to not only learn but to flourish and shine in the process.”

Brookes suggests most traditional schools—and, by default, the parents of students who receive their education through traditional schools—have become hyper-focused on “measurements” such as standardized tests and grades. Furthermore, she believes an emphasis on memorizing facts and reciting them back to prove proficiency misses the point.

“I think if we are only focused on whether the child got an A, we’re missing the big picture,” Brookes adds. “Was there truly any learning? At the Waldorf School of Princeton, we are helping students to think of learning as observing, recording, and inquiring. In that way, they develop the skill of learning. Oftentimes in our busy lives and our concerns to see our child succeed, we get too caught up on the A, but we are losing track of the goal, which is to learn. Grades are only one way of signaling a child’s capability, and they don’t always show how much learning has taken place.”

The key to ensuring that students receive a good education lies with the faculty. Each of the Waldorf School of Princeton’s educators receives professional training in Waldorf education, essentially becoming a master of their craft. Mentorship support reinforces the school’s commitment to developing strong, adaptable, caring, and competent educators. Just ask Solana Hoffman-Carter, a Waldorf School of Princeton alumna who recently returned as an educator. With Atkinson as her mentor, Hoffman-Carter has been thrilled to teach first-grade students.

“I can honestly say that from age three through the eighth grade were the best years of my growth and experience,” Hoffman-Carter shares. “I learned how to love the process of learning—and that’s carried with me and influenced every direction I’ve chosen in life.”

Hoffman-Carter considers her job as a Waldorf educator very much a creative endeavor. She considers it a gift to be able to share with future generations an educational experience that had such a profound and lasting influence on her life.

“My childhood was incredible, and so much of that is because of the experiential learning I was exposed to,” she says. “Learning should be a multisensory experience. At Waldorf, we spend so much time outdoors and participating in hands-on learning—opportunities students just don’t get in a typical classroom. I truly believe it was these experiences that got me to where I am today. I wouldn’t be the same person had I gone through traditional school.”

The Waldorf School of Princeton

1062 Cherry Hill Road

Princeton, NJ 08540

(609) 466-1970

Photography by Alison Dunlap

Published (and copyrighted) in Suburban Life magazine, August 2021.