The Path Forward

Brené Brown gives the “mapmakers and travelers in all of us” directions for a more meaningful, hopeful, and connected future.

A six-time New York Times bestselling author and a distinguished professor and researcher at the University of Houston, Brené Brown is deeply admired around the world. Her groundbreaking research aside, she seems like a trusted friend, the first person to call to share in the ups and downs of this journey we call life.

Brown’s storytelling, humor, and courage have earned her millions of global devotees. Her admirers include the more than 11,000 participants of the recent virtual Pennsylvania Conference for Women, which had been held in person at the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia prior to the emergence of COVID-19.

Brown’s latest book, Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience, aims to help readers reflect on their lives and make positive changes for the future. The keys to doing so, she says, are “to feel joy, express joy, and bring joy into a room during difficulties, and to find the ability to practice gratitude amid troubled times.”

Atlas of the Heart, an instant bestseller, explores the many emotions and experiences that define what it means to be human. It also walks readers through a framework for cultivating a life filled with meaning and a sense of connectedness—seemingly essential given the pain and turmoil of recent years.

“If we want to find the way back to ourselves and one another, we need the language and the grounded confidence to both tell our stories and to be the steward of the stories that we hear,” she explains. “Atlas of the Heart is for the mapmakers and the travelers in all of us.”

Brown has spent the past two decades studying courage, empathy, shame, and vulnerability. She shared some of her most recent learnings during her appearance at the Pennsylvania Conference for Women in November.

On why she wrote Atlas of the Heart …

“There are a couple of things that drove me to write this book. One of them is this quote from a philosopher that I came across 30 years ago when I was in college. ‘The limits of my language are the limits of my world.’ One of the exercises embedded in my curriculum-based research was to write a list of all the emotions that you can recognize in yourself when you’re experiencing them. We collected over 7,000 of these, yet the average number of emotions was three: happy, sad, and pissed off.

“There are a couple of things that drove me to write this book. One of them is this quote from a philosopher that I came across 30 years ago when I was in college. ‘The limits of my language are the limits of my world.’ One of the exercises embedded in my curriculum-based research was to write a list of all the emotions that you can recognize in yourself when you’re experiencing them. We collected over 7,000 of these, yet the average number of emotions was three: happy, sad, and pissed off.

“I’ve spent my entire life studying emotions, and I realized that when we don’t have the language to talk about how we’re feeling, ask for what we need, or convey what’s happening within us, we struggle. I have seen this in many areas of my research, doing leadership work and in my early days working with victims of domestic violence and sexual assault.

“I wanted to write a book to say to people, ‘I don’t know where you are, I don’t know where you’ve been, and I don’t know where you want to go. Heck, I barely know where I am and where I’ve been. But I think together we can become mapmakers, cartographers of our own experience so we can get to the places we want to be, and we can build connections.’”

On language and emotion …

“I share this analogy in the book. You have this pain in your shoulder that’s so acute and so excruciating that you literally see stars when it surges. It takes your breath away, and you finally manage to get to the doctor and she asks you, ‘What’s going on?’ In that moment your mouth is duct taped shut, and your hands are tied behind your back. You’re desperate to convey pain, but there’s no way to do it. It’s complex neurobiology. We can’t describe what we’re experiencing. We can’t ask for help. We can’t think or walk through the healing. Language is not just a means for communicating effect and emotion; language defines how we feel, and it shapes the emotion that we’re feeling.

“I share this analogy in the book. You have this pain in your shoulder that’s so acute and so excruciating that you literally see stars when it surges. It takes your breath away, and you finally manage to get to the doctor and she asks you, ‘What’s going on?’ In that moment your mouth is duct taped shut, and your hands are tied behind your back. You’re desperate to convey pain, but there’s no way to do it. It’s complex neurobiology. We can’t describe what we’re experiencing. We can’t ask for help. We can’t think or walk through the healing. Language is not just a means for communicating effect and emotion; language defines how we feel, and it shapes the emotion that we’re feeling.

“When I worked with school districts during the pandemic, big corporations, community activists, or mental health providers, everyone was so wrung out and had no language. They had no way to differentiate between despair, the feeling and fear that tomorrow’s going to be just like today no matter what we do, and every other complex emotion we’re all feeling at this time. We didn’t have the language, so it just came out as anger or tears.

“Language is a portal to new universes and universes of different choices, and second chances, and healing. I thought: I need this book now. I need my kids and my friends to have this language right now.”

On the link between vulnerability and connection …

“I think some of the greatest disruptions that I’ve created in the relationships I’ve been in is when someone makes a bid for connection and I’m so deep in self-protection and unaware of the walls I’ve put up that I either don’t return the bid or I squash the bid for connection. I think when we look at this theory that emerged from the data, three big pieces have to come together in order to cultivate meaningful connections. … The first one is a sense of grounded confidence.

On the link between vulnerability and connection …

“I think some of the greatest disruptions that I’ve created in the relationships I’ve been in is when someone makes a bid for connection and I’m so deep in self-protection and unaware of the walls I’ve put up that I either don’t return the bid or I squash the bid for connection. I think when we look at this theory that emerged from the data, three big pieces have to come together in order to cultivate meaningful connections. … The first one is a sense of grounded confidence.

“I come from a family where we didn’t talk about emotions; we certainly do now. Emotion was not only not discussed but seen as weakness. Vulnerability was weakness. You were either a sucker or the opposite. I write about this in the book that I actually thought something was wrong with me because I had an uncanny ability to understand the connection between what people said, what they were feeling, and what behavior was going to show up.”

On hope …

“Hope is the combination of three things: agency, goals, and pathway. High levels of hopefulness are correlated with goals, the ability to set a goal that’s tangible and reachable. Agency is our belief in ourselves to achieve that goal, and pathway, our ability to [create a] Plan B when Plan A doesn’t work. But I have to say that for everything that I wish would have been different growing up, there are a ton of things I’m trying to replicate with my own kids that my parents did.

On hope …

“Hope is the combination of three things: agency, goals, and pathway. High levels of hopefulness are correlated with goals, the ability to set a goal that’s tangible and reachable. Agency is our belief in ourselves to achieve that goal, and pathway, our ability to [create a] Plan B when Plan A doesn’t work. But I have to say that for everything that I wish would have been different growing up, there are a ton of things I’m trying to replicate with my own kids that my parents did.

“One of them instilled in me a tremendous amount of hopefulness. What we know about hope and hopefulness is that it can be taught. It’s often modeled at home, but if we didn’t get it at home, we can learn it. If you’re feeling a lack of hope, what I would suggest is getting really task-focused. What is a goal that you can set? How do you believe in yourself to achieve it? And if it fails, are you willing to try it again?”

On gratitude in times of plenty …

“It comes back to something I’ve been studying for 15 to 20 years. I think it comes back to a tangible gratitude practice. When we first quarantined, it was me, [my husband] Steve, my two kids, my mom, and her husband who had just gone into assisted living a week before COVID-19 hit. Then also my sisters and their families. There were a lot of us. The fact that we made it out alive is a miracle in itself.

On gratitude in times of plenty …

“It comes back to something I’ve been studying for 15 to 20 years. I think it comes back to a tangible gratitude practice. When we first quarantined, it was me, [my husband] Steve, my two kids, my mom, and her husband who had just gone into assisted living a week before COVID-19 hit. Then also my sisters and their families. There were a lot of us. The fact that we made it out alive is a miracle in itself.

“One of the things that we have always done as a family is to say grace when we eat. We sing it from a camp song, and we always go around the table and say what we’re grateful for. No matter what, the relationship between joy and gratitude is so empirically based. … It is not joy that makes us grateful; it is gratitude that makes us joyful.”

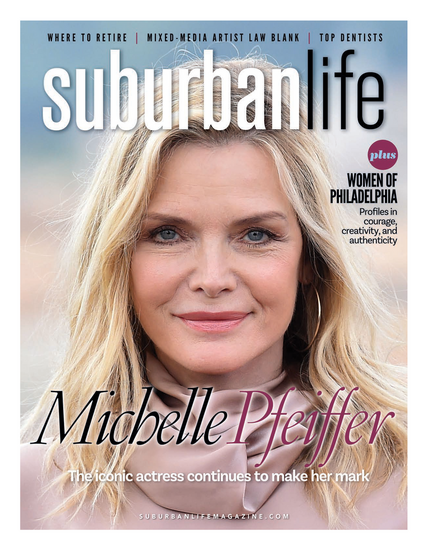

Photography by Randal Ford

Published (and copyrighted) in Suburban Life magazine, January 2022.

Published (and copyrighted) in Suburban Life magazine, January 2022.