Lost and Found

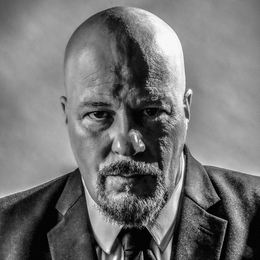

Having forfeited so much of his life to addiction, Robert Chiossi embraces a future rooted in recovery and reinvention.

“I was addicted to heroin. I lost my business, lost my wife, lost my self-esteem. Then, because of everything that happened next, I was sentenced to 10 years in prison.”

Robert Chiossi never imagined he would lose himself to heroin, never dreamed that he might one day face a decade behind bars for an offense he committed to feed his addiction. That’s what makes his story so terrifying—the notion that if it could happen to him, it could happen to anyone.

Chiossi grew up in suburban America, in a small town near Wayne, New Jersey. He came of age in a happy home with a love of music, but he always had the nagging feeling that he was somehow less capable than others around him.

An on-the-job injury caused his life’s trajectory to take a dark turn. When a doctor prescribed him Vicodin to contend with the pain, Chiossi was “off to the races.” His habit progressed to oxycontin, which led to a quick spiral into the jaws of “serious addiction.” Heroin wasn’t far behind, and his “descent into hell” followed.

“When I couldn’t beg, borrow, or steal for [heroin], it occurred to me that robbing a convenience store was the logical thing to do,” he recalls. “I didn’t see any other option. … When the cops found me, I folded. I didn’t have the heart to run anymore. I told the police everything, and it was like a weight lifted. I ended up in county jail.”

But his was only just beginning of Chiossi’s years-long saga of addiction, recovery, and reinvention. He would go to state prison, where he would embrace sobriety, rediscover himself, and work toward a college degree. He would also rekindle a love for the written word. Since being released from prison, Chiossi has become an author and a publisher, his dark and emotion-stirring tales published under the pen name Daemon Manx.

The story of Chiossi’s life abounds with tenderness and tragedy, its many twists and turns nearly impossible to capture in the span of a few pages. Following is an edited version of our interview, condensed for clarity and length.

Q&A

The stigma surrounding substance use endures, even though it affects pretty much every family in America. You mentioned you came from a nice family, a well-adjusted home. What holes you were trying to fill, so to speak, with drugs and alcohol?

Addiction was a symptom of a bigger problem. As an individual, I never felt complete. I felt like something was missing, uncomfortable in my own space. I had severe imposter syndrome; no matter what crowd I was in, I felt like everyone else was better. Stopping the addiction was the catalyst that allowed me to get in touch with what I was feeling. Later, when I started doing therapy, I came to the understanding that I’m not all that different, that my sense of inadequacy is a human condition. It was the way I’ve dealt with it that was the real problem.

The stigma surrounding substance use endures, even though it affects pretty much every family in America. You mentioned you came from a nice family, a well-adjusted home. What holes you were trying to fill, so to speak, with drugs and alcohol?

Addiction was a symptom of a bigger problem. As an individual, I never felt complete. I felt like something was missing, uncomfortable in my own space. I had severe imposter syndrome; no matter what crowd I was in, I felt like everyone else was better. Stopping the addiction was the catalyst that allowed me to get in touch with what I was feeling. Later, when I started doing therapy, I came to the understanding that I’m not all that different, that my sense of inadequacy is a human condition. It was the way I’ve dealt with it that was the real problem.

Tell me about the injury that kickstarted your addiction.

I was living in Florida at the time. My injury came while I was doing handyman stuff, little odds and ends. I was carrying plywood at the wrong angle and felt something snap in my neck. An orthopedist prescribed Vicodin, and I can’t describe the sense of ease and comfort that the first pill brought me. I was, like, “So, this is what has been missing.” I kept making these rules, like, I’m OK as long as I don’t do it at work, or it’s OK as long as I follow the prescription. It became so that I couldn’t go out to the movies unless I took Vicodin because I knew the movie would be better if I was on it. Then I met someone who was involved in oxycontin. … I thought I would sell a bunch and take some, but pretty soon I was taking everything I had and still running out. I was maxing out credit cards, lying to my wife, unrecognizable even to my own standards. Finally, it culminated in my wife saying she wanted a divorce. To me, she was trying to get in the way of my addiction, and you don’t want anyone like that around you. I moved back up to New Jersey at that point.

I was living in Florida at the time. My injury came while I was doing handyman stuff, little odds and ends. I was carrying plywood at the wrong angle and felt something snap in my neck. An orthopedist prescribed Vicodin, and I can’t describe the sense of ease and comfort that the first pill brought me. I was, like, “So, this is what has been missing.” I kept making these rules, like, I’m OK as long as I don’t do it at work, or it’s OK as long as I follow the prescription. It became so that I couldn’t go out to the movies unless I took Vicodin because I knew the movie would be better if I was on it. Then I met someone who was involved in oxycontin. … I thought I would sell a bunch and take some, but pretty soon I was taking everything I had and still running out. I was maxing out credit cards, lying to my wife, unrecognizable even to my own standards. Finally, it culminated in my wife saying she wanted a divorce. To me, she was trying to get in the way of my addiction, and you don’t want anyone like that around you. I moved back up to New Jersey at that point.

The pills were drying up, so I had a month or two of horrible white-knuckle detox, where I was miserable, out of my head and out of my skin. That’s when I ran into people who did heroin. Heroin is a hell of a lot stronger. I think I sniffed it for couple of days, and then I went right to the needle. I had made the decision that I would chase this until it kills me. But it wouldn’t kill me.

What was your frame of mind after you got arrested for robbing the convenience store?

Subliminally I knew it was the end of the line. My choice was taken away from me. First I went to the county jail, first-degree robbery, a slam-dunk case. …I didn’t have a decent night’s sleep for the first 40 days. I was put in a work program, working in the kitchen, and I got promoted to cooking the officers’ food. I look around [the kitchen] and see all the ingredients to make hooch, and a place where I can hide this. I put together a giant batch, knowing Christmas is coming, and I get caught. They drag me out of my cell, and now I’m in solitary. There’s nothing in the cell to read or occupy my time other than one pamphlet someone left behind, either accidentally or intentionally, about recovery. That was the lightbulb moment, with me thinking: This is rock bottom. I’m in a jail inside the jail.

Subliminally I knew it was the end of the line. My choice was taken away from me. First I went to the county jail, first-degree robbery, a slam-dunk case. …I didn’t have a decent night’s sleep for the first 40 days. I was put in a work program, working in the kitchen, and I got promoted to cooking the officers’ food. I look around [the kitchen] and see all the ingredients to make hooch, and a place where I can hide this. I put together a giant batch, knowing Christmas is coming, and I get caught. They drag me out of my cell, and now I’m in solitary. There’s nothing in the cell to read or occupy my time other than one pamphlet someone left behind, either accidentally or intentionally, about recovery. That was the lightbulb moment, with me thinking: This is rock bottom. I’m in a jail inside the jail.

I signed up for Narcotics Anonymous, Alcoholics Anonymous, and started going to groups. I was fortunate that they had them in county jail several times a week. I met an older guy who put me in touch with a sponsor, and over the course of the next 18 months in county jail, I worked the 12 steps and tried to get the best deal I could. I was told the best offer I was going to get is 12 years [in prison], and I would have to do 85 percent of that. So I go to court, with my court-appointed attorney, and the judge asks me if I have anything to say for myself. I stood up in my big orange jumper and said, “I did everything I am being charged with. I can’t take any of that away and know I have to go to prison. While in county jail I’ve been doing everything I can so I will not be the same man as the one who walked in, and I hope to bring my message to others.” The judge sentenced me to 10 years, and I would have to do eight and half of that. I was grateful for that. I was transferred to state prison. It was difficult and uncomfortable, but I did amazingly well there.

Did you ever imagine you would find yourself in that kind of position?

Never. Of all my friends, of all the people I knew, I thought I was the least likely to end up in that situation. Prison just wasn’t me; I always had a kind heart. Addiction took me so far out of who I really am. So I’m walking into state prison, a year and a half [after the robbery] and my head is clean, and now I’m in touch with who I am and who I want to be. The good thing about getting clean, and also the bad thing, is that you get your feelings back. I’m living for any letter that’s coming back to me. I’m voraciously reading and writing, devouring Animal Farm, 1984, The Grapes of Wrath, and Moby-Dick.

Never. Of all my friends, of all the people I knew, I thought I was the least likely to end up in that situation. Prison just wasn’t me; I always had a kind heart. Addiction took me so far out of who I really am. So I’m walking into state prison, a year and a half [after the robbery] and my head is clean, and now I’m in touch with who I am and who I want to be. The good thing about getting clean, and also the bad thing, is that you get your feelings back. I’m living for any letter that’s coming back to me. I’m voraciously reading and writing, devouring Animal Farm, 1984, The Grapes of Wrath, and Moby-Dick.

I got put on a unit for older men, and generally these are not the people you have to worry about in prison; generally they’re there doing the right thing. I met a guy named Marco, an older Italian dude from Newark. He brought me to church retreats, took me to Buddhist services. I recall going out into the yard, where everyone else is lifting weights, and Marco and I are in the corner doing yoga. He mentored me that way. Then one day someone knocked on the door and asked, “Would you like to sign up for college classes?” Yes, yes I would. I started taking English comp and English lit classes through a program called NJ-STEP, and that started me down the path of writing short stories in my cell. Quite a few of them are published now.

So I’m attending NA and AA meetings. I’m going to religious services; I call myself spiritual rather than religious. I’m writing. I’m keeping a 4.0 GPA. I’m a different person by this point. I kept progressing through the system, going to halfway houses, and got six months knocked off my sentence [because of COVID-19]. I was free in November 2020. In all I did eight years and one month.

Looking back, how do you remember the experience?

Had I not been arrested, I would have died. I always say I wasn’t sentenced; I was saved. Emotional sobriety takes so long to achieve. From 15 to 45 I was on something every day, and it takes a long time to reprogram the brain. The real tragedy is the time away from my family. I would talk to my mom on the phone [while I was incarcerated], because your mom is always going to love you, but my father was not interested, and my sister was not interested; I don’t blame them, because I was a despicable drug addict. One day I was on the phone with my mom and she’s crying, and she tells me, “I’m sick.” I know it’s cancer. She told me on a Saturday, and she was gone the following Tuesday. I had all these thoughts to come back and make things up to my mom, but I never got the chance.

Had I not been arrested, I would have died. I always say I wasn’t sentenced; I was saved. Emotional sobriety takes so long to achieve. From 15 to 45 I was on something every day, and it takes a long time to reprogram the brain. The real tragedy is the time away from my family. I would talk to my mom on the phone [while I was incarcerated], because your mom is always going to love you, but my father was not interested, and my sister was not interested; I don’t blame them, because I was a despicable drug addict. One day I was on the phone with my mom and she’s crying, and she tells me, “I’m sick.” I know it’s cancer. She told me on a Saturday, and she was gone the following Tuesday. I had all these thoughts to come back and make things up to my mom, but I never got the chance.

After I got out, my father and sister both started talking to me, so I saw there was a chance for mending those relationships. I live with my sister now, and I see my father every day; he lives in the next town over, and I go to his house every morning and walk his dog. I’ve been out just over two years now. My relationships have healed. I have rekindled a relationship with a girl who was my first crush. I’m still big on the program. A day or two a week I work in construction, but most of the time I’m editing and writing, putting out my own stories or other people’s through Last Waltz Publishing, my indie-horror publishing house.

Has your writing helped you process everything you went through?

I have a book coming out in April, Manxiety, a collection of stories I wrote while incarcerated—some fiction inspired by addiction, and some dark little memoirs. I hope the stories I write can provide hope for other people, finding alternative routes to addiction and recovery without having to go to the depths I went to. I also make videos about my experience and share them on social media.

I have a book coming out in April, Manxiety, a collection of stories I wrote while incarcerated—some fiction inspired by addiction, and some dark little memoirs. I hope the stories I write can provide hope for other people, finding alternative routes to addiction and recovery without having to go to the depths I went to. I also make videos about my experience and share them on social media.

If anything from my experience helps, even if sharing what worked for me helps just one person, maybe it was all worthwhile. The act of offering help to others is a way to help yourself, and I feel like I’m getting through to some people. It’s hard to be selfish if you’re thinking of someone else.

Photo by Jimmy Jeffreys

Published (and copyrighted) in Suburban Life, December 2022.