Until several years ago, Kintnersville resident Ruth Stonesifer was known mostly for her quilting skills and for raising two sons.

“I was skating through life, not paying enough attention until it slapped me on the head,” she remembers. Then came the horrific day that she learned her son, Army Ranger Kristofer, had been killed in the crash of his Black Hawk helicopter on a dusty Pakistani airstrip near the Afghan border. Now, a little more than eight years after the event that shook her world, Stonesifer finds herself at the helm of a national organization whose membership no one wants.

As president of Gold Star Mothers, it’s her job to help educate the public to the sacrifices of so many military personnel and to guide a network of supporters for their parents. Gold Star Mothers was founded after WWI by the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defenses. Its members were identified by the gold star sewn onto a banner hanging in the windows of their homes or on a black band worn around the arm.

Today the GSM continues to advance veterans’ rights, promote patriotism and peace, and perhaps most importantly, serve as support for other women who have lost their children to war and help to perpetuate their memories.

Quilts, bills and banners

Stonesifer didn’t just walk into this position. She’s worked tirelessly as an advocate for those families who have lost a loved one who was serving on active military duty. Her first foray into the public arena was to join a national group that creates quilts to send to wounded soldiers. Before long, she had coordinated a monthly quilting group that meets at Byrne Sewing Center in New Britain, which donates the space and machines for about 20 women—and even a couple men—who sew the quilts, creating about 20 Quilts of Valor each month—a total of 500 in the past five years.

“I have learned that the biggest thing is to take the time to heal. But then you realize you’re still a part of the human race and you get out in the world again,” she explains.

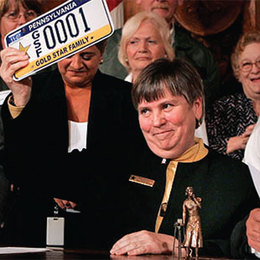

In addition to leading the quilting group, Stonesifer pushed a bill through the PA legislature to create specialized license plates for Gold Star Families—immediate family members of someone killed while on active duty are eligible to apply for one. At the time it was passed, in January 2003, only seven other states had Gold Star plates, but she had done her due diligence, and the bill fairly flew through, allowing approval in less than 10 months.

“I had a plate on my car in October,” she says proudly. “This snowballed nationwide after Pennsylvania came through. There are more than 40 states with this awareness plate now,” she adds.

Rounding out the trifecta of awareness initiatives Stonesifer has implemented are the banners hanging around the Doylestown Courthouse. She originally saw banners with the images and vital information of military personnel killed since Sept. 11, 2001 in California, and thought it would be something good for Pennsylvania. These Hometown Heroes banners were first hung in Harrisburg, and then she got the backing of the Bucks County Commissioners to create banners for the 18 county soldiers who had lost their lives.

“The county paid for these banners, and pledged they would remain perpetually funded,” she says. “Everyone finds their own mission and you know it immediately when you do…We go to bed safe every night because our children and others are in harm’s way…this is the power of our democracy…I’ve experienced this evolution thanks to Kris’s inspiration.”

The GSM

Keeping war casualties at the forefront of peoples’ minds is important to Stonesifer. The families of these soldiers form an invisible network that few know about in part because of all the privacy acts in place. After the Department of Defense notifies her of a death, Stonesifer contacts the state representative, who attends any funerals or memorial services, sends out condolence cards and speaks with the family about the network of support that exists.

“This is a grassroots effort,” Stonesifer explains. “It’s too important to remain unknown.”

The group’s main focus is education. “We’re not a grief group. We support each other and help find the positive in the negative, which we must do to honor our sons and daughters—the greatest patriots.”

Even after all this effort, Stonesifer says she would like to do more locally with veteran’s groups, and continue to work with different projects such as Wreaths across America, which places wreaths on veteran’s graves in December. A photo of the mass wreath-laying at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, DC, flew around the Internet several years ago, creating almost instant recognition for the group.

Working through her own grief, Stonesifer has found ways to honor her son, help others and create a new life for herself. She will never forget Kristofer or the many others who sacrificed their lives—and if she has her way, no one else will either.