The fire in his belly burning hotter than ever, Ed Rendell simply refuses to go gently into that good night. And we are all better off because of it.

Whereas some politicians step quietly into the background after their terms expire, Rendell has remained very much in the public eye, jamming his schedule overfull with jobs, causes and interests that suit his style. In truth, he’s likely just as busy now as he was as Philadelphia’s district attorney or its beloved mayor or, most recently, governor of the Keystone State.

These days Rendell spends his time practicing law with national firm Ballard Spahr, analyzing politics for NBC and Eagles games for Comcast SportsNet, co-chairing Building America’s Future, which is an organization devoted to strengthening the country’s infrastructure in urban and rural areas alike, and, of course, trying to ignite a revolution that would get America back to taking risks, making tough decisions and speaking its mind.

Helping the nation rediscover its boldness is one of the main reasons he wrote the recently released “A Nation of Wusses: How America’s Leaders Lost the Guts to Make Us Great.” (“For a book that has no sex and no violence,” he says, “it’s doing very well.”) The title of the book stems from an incident in December 2010, when a football game between the Philadelphia Eagles and the Minnesota Vikings was cancelled due to a looming snowstorm, long before a single flake had fallen. Afterward, an incredulous Rendell rather famously proclaimed that America was becoming “a nation of wusses.”

He may be right, but it’s not too late for us. Suburban Life recently sat down with this New Yorker by birth and Philadelphian by choice (now 68, he came here at 17 and, essentially, never left) to discuss how America—and, more so, its leaders—can get back its boldness, his next move and, of course, his take on the Eagles’ Super Bowl chances this season.

SUBURBAN LIFE: The book’s title is as provocative as the statement that gave birth to it, after the so-called Eagles Game that Never Was.

ED RENDELL: I had never heard of cancelling a football game for bad weather. The San Diego Chargers in the ’70s played a game at Cincinnati for the AFC championship and the wind chill was minus 63 degrees and they still played the game. The Eagles in 1951 played for the NFC championship against the Cardinals in an 11-and-a-half-inch blizzard. Nobody even thought of cancelling the game, and [halfback] Steve Van Buren, who was the equivalent of Tom Brady at the time—he was the star Eagles player and the star of the NFL—he took two trolleys and a bus to get to the stadium in time to play the game. And I thought to myself, If this was Green Bay or Minnesota or even Pittsburgh or Buffalo, people would say, “What? They cancelled the football game?” It bothered me, but when I reflected on it for a second, I realized that it sort of became a symbol of what’s happening to us as a country.

One example I gave was our relationship with China. I’m all for free trade … but China has without a doubt manipulated their currency to give Chinese businesses a huge advantage over American businesses. They have stolen our intellectual property, and the Chinese government has done nothing to police that. They dump product in the United States to undercut our businesses and drive them out of business so they end American competition, and we don’t do anything. We say, “Please stop.” And the answer is, “We can’t do anything because they own all of our debt.” Well, of course that’s true, but we buy most of their product, and if we stop buying their product their economy would go into the crapper in four months. So we have as much leverage on them as they do on us. It’s time to stand up and say, “No more currency manipulation. If you continue to do it, you’re not going to send product into the United States.” We just don’t have the backbone to do that.

When did this “wussification” start occurring?

It happened with the advent of 24-7 media, because every act is reported almost instantaneously. Whereas the media used to report the news, the media is now in the opinion business, and the opinions are sledgehammers. You’ve got right-wing opinions, progressive opinions, and anyone who wants to get together and do some things that are risky but necessary gets the [stuffing] kicked out of them.

There’s an inability to do anything that’s risky at all. The reason this is so poignant is that this nation was built by risk takers. We were a bunch of shopkeepers and farmers who had the audacity to think we could take on the greatest army and navy in the world—the British—and we knew what the consequences were; the men who signed the Declaration [of Independence] knew that if we lost that they would be hung, and yet they did it. They were the ultimate risk takers. We were risk takers when we built the Erie Canal, when we built the Hoover Dam, when we built the railroads and the interstate highway systems. We were risk takers, and we did big, bold things.

JFK took a huge risk when he said we’ll put a man on the moon before the end of the decade. My favorite Kennedy quote was when he made that announcement, he said, “We do these things not because they are easy but because they are hard.” So this nation of risk takers has turned into a nation of wusses. And I don’t mean the people, necessarily. We also don’t respect the intelligence of our people. … We don’t have the courage to tell people the truth.

So what can we do about it?

After the election, whoever is the president elect has to lead and say, “Look, the only way we’re going to meet the challenges, the only way we’re going to get through it without falling over the fiscal cliff, is for us to take bold steps, which involve taking risk and ticking people off, but I’m going to lead and I’m going to take most of the weight and you guys follow and do the right thing.”

Your “nation of wusses” comment probably got more press than the cancelling of the game. Were you surprised?

I had to laugh. I quoted a Daily News reporter, Will Bunch, who ran a story about it the next day, and [his story] basically supported what I said. He said, “If this was China, 65,000 Chinese would have walked to the game doing advanced calculus as they walked.” I repeated that quote and newspapers in Shanghai and Beijing quoted me, saying it was my quote, but I was stunned to think that a comment about a football game would wind up in newspapers in Shanghai.

For those of us who haven’t gotten to the book yet, what takeaways do you think people will come away with after reading it?

I wrote the book for three reasons. First, particularly for young people, I wanted to communicate that although public service is very difficult—it’s low pay, bad working conditions, you’re scrutinized all the time, often you’re in can’t-win situations, it’s highly pressurized—despite all those things, it’s a wonderful way to live. Your work product, your talent and your energy is going into changing people’s lives on a daily basis. I hope it would inspire people not just to run for office but to work in government, to work in nonprofits, to put themselves in a position to get that feeling.

The second reason I wrote the book was to debunk this idea, which has gained ground politically, that government is the enemy, that government can’t do anything right, that the best government is the least government, that we don’t want the government spending money. Using myself and others as an example, government when it’s targeted and effective and cost efficient can do wonderful things to help people—to create opportunities, to protect the most vulnerable citizens, to promote growth, and I think I demonstrated how I did it and how other people along the way have done it.

The third takeaway is that, yeah, we need leaders who are going to have the courage to start taking some risks and not worry about protecting their own job, and that’s an important part of breaking the stalemate and the logjam that exists not only in Washington, D.C., but in most state capitals. For us—we the people—we need to continue to reinforce and support those politicians who do take risks. We can’t expect them to be risk takers if we punish them for every risk that they take that doesn’t pay off. It’s almost like we the people have to give our leaders permission slips to take risks.

Given your nature and your way of doing this, what path do you think you would have followed if you hadn’t gone into politics, or law for that matter?

I think I would have been a pretty good PR person or promoter or advertising person. As mayor I spent a lot of time promoting the city, and I enjoy that. I also think I might have made a good developer, too. I sort of have an ability to see big things and look down the road a little bit. … Politicians who are active in economic development are sort of co-developers.

What’s the biggest lesson you learned from your time in Philadelphia politics, or even in Harrisburg?

Hopefully you learn from your mistakes. My biggest mistake was the one time I wussed out when I agreed with the legislature to give them the pay raise [in 2005]. They had threatened me that if I didn’t sign the bill that they would never pass anything I was interested again, and I had five years ahead of me. I should have realized it was a bluff, and I should have called their bluff, and I didn’t. Lesson No. 2 I learned, and maybe this is just my style of management, but it’s very important for the person in charge to be involved in everything—one, because the person in charge usually gets to be in charge because they have a level of talent and experience; two, because in the end you’re going to take the hit for it no matter what.

A perfect example was when I-78 froze over [in the winter of 2007] and we had all those people trapped. I didn’t find out about it till 7 o’clock at night, and people had started to be trapped in their cars with no way out at 2 in the afternoon. The reason I didn’t find out about it is that no one in the chain of command—the PennDOT secretary, the PEMA (Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency) chief—called me or my chief of staff; they tried to deal with it without bumping it up to us. I found out because a citizen called into the governor’s residence and said, “I’m trapped here. What’s the governor doing about it?” As soon as I found out about it, I declared an emergency and called out the National Guard and sent the guard by foot into the people who were trapped on the highways, evacuating anyone who was cold and sick, giving blankets and water to the rest, and that averted a humanitarian tragedy. … Leadership matters. Sure, it’s important to delegate and you should delegate, but you have to be involved in the ultimate decision making.

So, as one of Philadelphia’s favorite sons, what would you say is the best thing about Philly?

The best thing about Philly is still the people. The people are resilient, they care very deeply about their city, and they’re willing to sacrifice. When I became mayor we cut everything, and my message to the citizens was, “Don’t [complain]. These cuts are necessary but if it works we’ll be able to turn things around down the road,” and people understood. There were some protests, but they accepted the cuts because they knew we were trying and they wanted to give us the time to do it. I think just as we’re more passionate about our sports teams than most cities, I think we’re more passionate about the city than most cities. One of the reasons for that is we’ve got so many homegrown people. I don’t know what the percentages are, but my guess is that of the top 10 cities in the country Philadelphia may be No. 1 in terms of the people who were born here and stayed here.

If you could go back and change one thing about Philly what would it be?

Two things: education and crime. As governor, one of the areas where we were doing a great job was with education. Sure, we had a way to go but we were making awesome progress. If we had a great public-education system, it would have two effects: It would reduce crime; and it would allow middle-class young people—white, black, Latino—to continue to live in the city and send their kids to city public schools. Right now what happens too often is young people have flocked back to the city … and when it becomes time for their kids to go to kindergarten, unless they can afford to send their kids to private schools, most of them move out to the suburbs, not because they want to live there but because they want their kids to have the education. We need to keep that young professional class in the city, and education is so important to everything. Education is the long-run solution to crime, though I would also add significantly more police.

You’re busy enough as is, but what’s next for you?

I want to continue doing what I’m doing. I love the work I’m doing with Mayor Bloomberg on Building America’s Future. I love the work I do for NBC. I love making speeches and getting paid for it. I love the work I do for my law firm, and they’ve been very good to me in the sense that they allow me to bring in clients that I want to bring. I also teach at Penn and I do the sports shows, so I do a lot of different things. I’m enjoying my life.

The only two jobs I would leave what I’m doing for would be—not necessarily in order of importance—baseball commissioner, which in some ways is my dream job, and secondly would be if Hillary [Clinton] runs in 2016, I would be her campaign manager and I wouldn’t charge her a dime. And then if Hillary got elected I might consider doing something with her in D.C., but there’s no certainty she’s even going to run.

Last question, Governor, based on your work with Comcast SportsNet: How do the Birds look this year?

They look terrific. Had [offensive tackle] Jason Peters not gotten injured, I would have picked us as the NFC representative in the Super Bowl. Without Jason Peters it’s up in the air, but if Michael Vick can stay healthy and play 16 games, I think we have a chance to go all the way. That’s a big if, though.

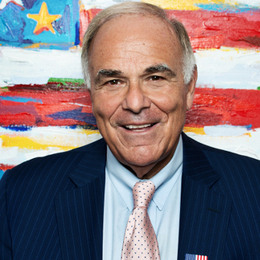

Photograph by Jeff Fusco